- Home

- dee Hobsbawn-Smith

What Can't Be Undone Page 13

What Can't Be Undone Read online

Page 13

As we ate our macaroni and cheese, Jill startled me by announcing, “Fanny gave away her lunch today.”

Mom, her face shadowed by the potted fig tree beside the dining room table, immediately looked awake. “Tired of egg salad, Fan? Your favourite.”

“Carrots, not sandwiches,” Jill said, her lisp making her words fuzzy. “She gave them to a big horse.”

Mom sighed and picked at her lettuce. She’d shrunk since Dad’s death. I’d given up trying to get her to wear anything other than baggy jeans and one of his grey plaid shirts buttoned over her camisole. At the recent parent-teacher interviews, I’d worried when I saw how dull her skin seemed beside my PhysEd teacher, who glowed in a flowing Indian cotton dress and scarf. But I couldn’t get her to eat more. All she wanted was salad and mint tea.

Mom didn’t ask questions, but I felt an unfamiliar hint of guilt, worried about what my sister might say next, careful to not mention the horses or their owner as Jill climbed into the bunk above me and we settled down to read. I went to sleep with my fingers flat across the tender skin of my belly, caressing the jut of my pelvic bone, and dreamed about the tall man with the narrow hands.

The next day, I sent Jill ahead of me when we got off the afterschool bus. “I’ll be right behind you,” I said and shoved her gently homeward. “Just go have a snack. Soon as I’m home we’ll read the next chapter of The Red Pony.” Then I walked up the horseman’s lane with the apple I’d saved from my lunch. I hovered at the gate, twisting the straps of my backpack until the man emerged from the barn.

“You again. You got no schoolwork to keep you out of trouble?” He snapped his fingers at the bay nosing my apple. “This here’s Nero. What’s your name, girlie?”

“Fanny.”

“You want a job? I could use an exercise girl. Muck out the barn, clean tack, take the horses to the lake. Some gallops here on my track. Think you could handle that?” A searching look from beneath the brim of the cowboy hat. “Five bucks an hour. Call me Roy.”

“I have to ask my mom,” I said, my breath caught in my throat, and ran to catch up with Jill.

None of my classmates rode horses but I asked my cowboy-crazy best friend Sheila about Roy. She told me during biology class that she’d heard some gossip at the record store. He liked to hire girls. Had three kids. A wife who’d been his exercise rider back in the day. Her voice rose half a peg. “Why the interest?”

“Just a job,” I hurried to say. There was nothing to admit, I told myself fiercely. Nothing. But I couldn’t explain away the flutter of doves’ wings in my chest.

“Boring,” Sheila said. “He’s so old!”

Inwardly, I modified her words. He was a man. Not a boy.

Sheila tugged her skirt up a little higher and turned the talk back to sex while she stared at our teacher as if he was a butterfly she wanted to pin, her back arched so her breasts pushed forward. I still felt acutely self-conscious about my own breasts and hid them under loose t-shirts, but Sheila wore hers proudly, like medals she had earned, their soft swellings edged with a lace bra clearly visible from the neckline of her peasant blouse. Waving a glass slide like a conductor’s baton, she said, “Fanny, why don’t you just let one of the boys kiss you and get it over with? Peter, maybe, he’s always talking about you. Don’t be such a priss. Everyone does it.”

I turned my face to the microscope, blushing as she recounted her latest date at a recent concert, kisses and surreptitious touching, fumbling hands and mouths to the backbeat of steel guitars and cowboy tenors. But my body paid attention in a way it hadn’t when Mom had coloured and stumbled over words during “our talk” several months before Dad’s death. She’d brought home educational films from the library, both of us hemmed inside our chairs as we’d watched images too graphic to be mistaken for just another biology lesson. I couldn’t meet her eyes when she turned off the VCR. How could I equate that with the stirrings I felt, with my electrified skin, the shivering fine hairs along my bare arms? But each time I witnessed Peter’s red-faced embarrassment when I accidentally caught his eye at the bus stop, I dismissed him. A boy. His body thick, his face pocked. Graceless. I thought of the lithe horseman, and wished again that Dad was still alive, although I might have hidden this particular mystery from him. Now, I believe he’d have waded in with advice despite his discomfort. He’d been that kind of man, matter-of-factly brave beyond bulls.

The following Saturday morning, I leaned my bike against Roy’s barn wall and spotted him through the kitchen window as he waved me into the house.

The house smelled of coffee, horses and babies. Roy eyed me. “You bring your helmet?” He nonchalantly arched his arm in my direction from his seat at the table. “My wife, Lisa. This is Fanny.”

I looked into a pale face, wrinkles beginning to erode the skin around mouth and nose. A mane of uncombed black hair. Amber-flecked eyes, a mouth like a whip. She was an inch shorter than me, diaper-clad baby on one hip, half her face shuttered by the fall of her hair. A pair of brown-haired boys, about four years old, identical except for the colour of their t-shirts, romped on the floor at her feet, yelping and laughing.

Roy tipped an eyebrow toward the counter. “Want coffee? Help yourself.”

Dad had been a coffee hound, but he’d refused to let me do more than sniff his morning mug. This was my first taste. It was unexpectedly bitter. I wasn’t sure I liked it, but I sipped as I watched the boys wrestle. My bones felt too big for my body. In that hothouse of a room, I ached for my uncomplicated dad, his self-effacing shrug and half-sideways grin that showed his chipped tooth and smoothed the edges of everything he did.

Ten minutes felt like an hour by the time Roy stretched to his feet. I set down my half-full mug with relief, its thump echoing into the silence. Lisa stood wordlessly at the sink as I thanked her, her child wide-eyed on her hip. “It’s Derby Day, Secretariat’s running,” Roy said to her, then whistled sharply at the twins. “Tell them boys to watch their cartoons early. I’ll be in later to see the race.” They stopped wrestling, looked up from the floor at him, then sideways in unison at Lisa. She stubbed out her cigarette, her face slamming shut as she studied me as closely as Roy had at the gate. I sniffed and picked up my crash helmet. What kind of woman would let herself get so dog-eared? But even as the thought floated through my brain, I could picture my mother’s haggard face.

“You hear of Secretariat, girlie?” he asked as we walked to the barn.

I shook my head. I didn’t know racehorses other than what I’d read in Dick Francis novels, although my bookshelf always overflowed, National Velvet leaning on The Black Stallion. Black Beauty beside The Art of Horsemanship, A Leg at Each Corner lying open at the first cartoon pony.

“You will. This is Alexander. Saddle up.”

At the sight of the red stallion in the barn, I forgot what I’d been thinking. He didn’t flinch when I tossed on the saddle, but he leaned obstinately away when I raised the bridle. “You’re too short,” Roy said, gestured toward an old wooden stepstool beside the wall. “Use that, it’s hers. Lisa’s.”

I dragged the stool into the centre of the aisle, climbed up, slid the bit past long slanting teeth, smoothed the leather straps behind tufted ears. Outside, Roy gave me a leg up, then held the stirrup iron as I fumbled my boot into it. The exercise saddle felt absurdly small, nothing to really sit in, just a bit of leather to perch above.

“He likes to come out fast, but he don’t go far,” Roy said. “Just take him three furlongs.”

I didn’t get a chance to ask what a furlong was. Roy led the horse onto the narrow dirt track that followed the farm’s fenceline, turned him loose and chirruped once. The long ears ahead of me flickered and Alexander erupted into a gallop. I grabbed what wisps of mane I could and steadied myself in the tiny saddle, my legs tucked up like a grasshopper’s. I glanced down once. Beneath us, the black soil rushed past, so close. Those four flashing legs all that kept me safe. I raised my head, felt the wind whip my grin from my

face and toss it behind us. A wince of guilt slid through me; even at her fastest, Meara was a slug compared to this horse.

He abruptly slowed into a shuffling trot, and I had my breath back by the time we stood in front of Roy. He pulled his cigarette out of his mouth and cocked his head to look up at me. “Not bad, girlie. Want the job?”

School finished. I promised Sheila I’d visit her in town, knew I wouldn’t. She’d only want to debate how far to go with her string of impatient guitar-playing boys. Instead, my summer routine unfurled in stinging sweat, the warm muddle of leather, horses and box stalls, the growing tension in my body. Mom had acquiesced when I told her I’d found a job exercising racehorses. “Be home in time to mind Jill when my evening shift starts,” she’d said, “and just be careful.” I knew she didn’t mean speed or protecting my teeth or eyes. I resolutely blocked out thoughts of Dad. He might’ve liked Roy, but not as my new boss, although the job itself would have tickled his fancy.

Mornings, I joined Roy and Lisa in their sunny kitchen, Roy’s feet in his dusty cowboy boots propped up on a chair, Lisa chain-smoking on the window bench, the baby and twins on the floor. “That Secretariat,” he’d say, shaking his head, “Done it again. The Triple Crown last month, the Arlington Invitational last week. Never seen anything like it.” After he drank two cups of coffee, the Sun’s daily racing pages fallen to the floor beside the baby, Roy led me out to the barn.

Every day I watched Roy walk in and out of stalls, denim jeans taut across his narrow hips. I stopped biting my nails and stripped off my stained work gloves whenever I thought he would hand me a pitchfork or tub of saddle soap. My skin shivered as he ran his hands down his horses’ legs. “Here, girlie,” he’d beckon, then grab my hand, pulling me to my knees beside him where he squatted in the straw. His fingertips firm on my hands, guiding them down the horse’s shin. “Feel that tendon along the cannon bone? Gotta watch it for heat or swelling.” He dropped my hand and pushed himself to his feet. I gasped inside as he walked away.

Some days, I galloped Alexander or Nero around the rough track, Roy’s cattle watching us stupidly from the next field. Other days, I took Nero to the Vedder canal and we waded in murky water that splashed up onto my boots. On the far bank, brambles hung, jungles of thorns and canes glittering with blackberries. Most days, I daydreamed about Roy, imagining something less tarnished than Sheila’s casual experiments. I had to pull Nero to a halt before I rode back onto the yard, think about the muscles of my face, rearrange them into a mask while I cleaned the mud from his fetlocks and hooves.

I didn’t call Sheila. I collapsed into my bed after late suppers, ignoring Jill, pretending to sleep so she wouldn’t ask me to read or brush her hair. Roy and his horses galloped into my dreams and I woke each morning with shamefaced pleasure, anxious to see them again.

One morning in late July, Alexander was tied in his box stall when I arrived. “Two mares comin’ over,” Roy said over coffee. He looked at me inquiringly. “Ever see a stallion cover a mare?”

I blushed and shook my head, acutely conscious of Lisa. But when I looked up, she was gazing intently at her husband, not at me.

“Thought not,” he said easily. “Too young. You’d best go home.”

On a humid August evening after supper, I needed to get out. Jill was whining. “There’s nothing to do. I’m hot.”

I ignored her pouting as I saddled Meara. “There’s ice cream in the freezer. You can watch My Friend Flicka again. And stay in the house!” I yelled as I left, guilt pricking at me for abandoning her despite Mom’s specific instructions. Just an hour.

At Roy’s, I tied up Meara, saddled Nero and urged him around the track, my mind flattening with every stride, then shepherded him into the pasture to graze. Roy ambled up and leaned against a dogwood tree, cigarette hanging loosely from his mouth. He tipped his cowboy hat back and watched as I tidied the saddle, running the belly-band between clanking stirrups, looping bridle reins, sponging away sweat stains. His hands toyed with a mane comb. Finally, when my skin was twitching from his silent inspection, he pulled his hat forward so most of his face was in shadow. “Trailerin’ to Osoyoos races end of the month, Fanny. You comin’?”

“To groom or to ride?”

“Groom. Some things you still too young for, girlie. Not for much longer, though, eh?” His brown eyes narrowed, barely visible beneath his hat brim.

“I’ll ask my mom,” I said, but I knew what she’d say. I put the saddle away, swung onto Meara and kicked her into a canter. No wave for Lisa, invisible behind her kitchen window, but I felt Roy’s eyes.

Instead of going home, I turned Meara along the canal’s flat shoulder, hoping to ride my body into exhaustion. The valley’s green shoulders were lush from the summer’s rain. Cormorants were fishing in the shallow water, blackberries ripening, but even from Meara’s back, I couldn’t reach the best where they dangled, protected by spines of barbed wire and bramble.

Darkness had arrived by the time I unsaddled and brushed Meara. Jill was asleep on the couch, the television blaring. I picked her up and hauled her into bed.

The next morning, steamy unfallen rain hung over the valley, blocking sight of the hills. Jill, at the table eating dry cereal with her fingers, turned to me and sing-songed, “Fanny has a boyfriend, Fanny has a boyfriend!”

“Shush! You’ll wake Mom!” I said, pushing her. “And I don’t! What are you talking about? You don’t know anything.”

It was too late. Mom came into the kitchen, rubbing her eyes.

“Jill says you were out last night. Where were you?”

“Riding. Sorry, Mom.”

“You can’t leave Jill alone. It’s not safe.”

“I didn’t mean to be gone so long.”

“Don’t do it again. And there’s a phone message for you from Lisa. You must have missed it when you were feeding Meara. She said Roy’s gone to the auction. She needs coffee beans and wants you to stop by the village’s coffee bar on the way to the farm. Fanny, you’re too young to be drinking coffee. You aren’t, are you?”

I didn’t answer. Just the thought of parking my bike in front of the coffee bar and walking into its heavy air made my chest tighten. Dad had always smelled of coffee. In the days that followed Dad’s death, Mom had wandered the house, playing “Some Day Soon” over and over, carrying around a mug of coffee and a photo of him. I had stayed in my room, crying, not crying, feeling like I should be crying. Trying to memorize Dad. How his ears had stuck out under his Smithbilt. The feel of his stubble on my cheek. His raptor’s profile sliding into a smile as he concentrated on making Mom laugh.

I fidgeted with my riding whip, nudging my boots with my toes. I could just see Mom where she stood in front of the kitchen window. Her hair, two shades darker brown than mine, was pulled into a severe ponytail and her shoulders hunched around her ribs like sparrows’ wings.

“Fanny, I know you like this job. And we can sure use the money you’re making. But six hours a day six days a week is too much for a teenager. Plus you’re ignoring Jill and your chores here. When did you last read to her? Or give her a riding lesson? School starts in just a few weeks. Jill needs you, too.”

I grabbed my lunch from the fridge and scuttled out the door. I could see Mom’s angular frame, kettle in hand, through the window as I climbed on my bike. All the way to the coffee bar, I fretted. What would Mom think if Jill repeated her nonsense?

Lisa stood at her kitchen counter. “Thanks,” she said, and dug in her purse for money as I handed her the beans. I had rushed in and out of the coffee bar to buy them without letting myself think about Dad. “It’s hard to get out with the kids while Roy’s got the truck. And he don’t shop.” Her voice was slow, almost a whisper.

It was the first time she’d addressed me directly. I covertly studied her face, wondering if she missed riding, but when she flicked her hair out of her eyes, I lost my nerve and didn’t ask. In the hallway, the stroller, garish with dangling toys, blocked acc

ess to a door. Behind it, I could hear the twins, thumping and roughhousing. The air in the kitchen was as weighted as the inert baby on Lisa’s hip. She moved like a lame horse, the baby’s back slumped into the curve of her elbow, her free hand rattling beans into the grinder. “Want coffee?” The beans whirled, stopped. Her words dropped into the silence. “He ask you to go to Osoyoos?”

“Nero’s waiting in the barn.”

“He’ll never let you ride in a race.” Lisa’s voice cracked, splinters following me out the door.

I groomed and saddled Nero, headed up the long hill toward Cultus Lake. What did she think about all day? How did she stand it, cooped up with those kids? I thought of Jill, how quick I’d been to leave her alone. Mom, burying herself in long hours at the cannery. Dad. He’d called us “his littlest bronc busters,” had loved the hours he’d spent with us, Jill beside him as he’d shouted instructions to me aboard Meara.

On the grassy strip at the lake’s edge, I stripped off the saddle, shed my jeans and dropped them in a heap, slid onto Nero’s bare back. I told myself again that I’d never have kids as I kicked Nero’s ribs, urging him into the lake. The water shocked away thought, then burned like ice. As Nero swam, my torso swayed, naked thighs tensed around his ribcage, my skin aching with more than cold. I believed I knew what Roy wanted when he watched me. No one had ever looked at me like that before.

When Nero plunged up the bank, we were both panting and breathless. I slid off and leaned against his shoulder, water dripping down my skin like melted glass, my legs jelly. I ran my hands down his tendons, one after another as Roy had taught me, lifted his hooves and picked them clean, then struggled back into my jeans for the soft ride back, my mind emptied.

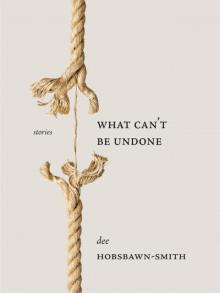

What Can't Be Undone

What Can't Be Undone