- Home

- dee Hobsbawn-Smith

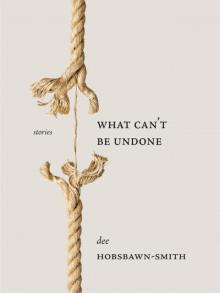

What Can't Be Undone Page 11

What Can't Be Undone Read online

Page 11

The boy skips around to my side of the cart, smiles and plants a kiss on one cheek, then the other. As he saunters away among the pink blossoms, his voice trailing off like an unfinished melody, “Merci beaucoup, ma tante,” I completely forget about my chest. I don’t have a Mother Superior to go to, so I go straight to the Mother, how I think of God, really. Old Soeur Jeanne-Marie always said that women hold up the sky, and from what I’ve seen in the world, she was right. How could God not be the Great Feminine, the Mother of All? I still believe, but I no longer wait for Her to solve my problems, I haven’t since I left the convent. So I pray to Her. Is this the child I never had, Mother? I don’t get an answer. Didn’t expect to. I just hope the boy will come back. The hot knife-edge pains, I ignore again, as I have over the years. For weeks and months to come, in my private daily conversations with Her, a jaunty black-eyed boy will feature prominently and unexpectedly. I’ve learned that love cuts as deeply as those other invisible blades.

I arrived at the convent’s orphanage in North Vancouver as a baby, sang French nursery rhymes, then Piaf and Aznavour’s love songs, with Soeur Jeanne-Marie, learned long division from Sister Agnes. The convent bell’s ringing amplified how much I longed to know my own mother; the nuns told me nothing of her. When I finally joined the order at twenty-five, the sole regret I attached to the order’s requirement of chastity was that I would never have a child, a family of my own. Even obedience, if I could have kept my mind attentive, seemed no great struggle.

Not many women take the veil these days, so those who do fill many roles — I was both apprentice cook and gardener. Daydreaming in the garden instead of weeding, I would look up to find Sister Francesca standing in front of me, pointing at my basket and rasping, “Have you washed those greens yet, sister? Work is waiting.”

Francesca was a Reuben-esque woman, as generous to me as God had been to her, with the biceps of a weight-lifter, thick white hair and sun-reddened skin, a hooked nose, the long blue gaze of patience. She was a German butcher’s daughter, must have been stunning as a young woman, and passed her family’s secrets on to me — my sausages for the cart are made as she taught me, with freshly ground pork, salt, maple syrup, chopped herbs and peppercorns, garlic, stuffed into pork casings and smoked over apple wood. When my knife slipped or I threw trimmings into the trash, she just smiled and patted me. “Well, young sister,” she’d say in her stone-edged voice, and she’d wipe her butcher knife on the cloth at her hip, rescue the meat, wash it before grinding it. “Now you know better. From little, much can be made.” Francesca and I fed the nuns, but also the convent’s guests; they were few and far between, though, and loneliness walked with me in the garden.

“Did you ever want to have a child?” I asked one muggy summer day as we trimmed a pork shoulder, sweat sticking to my skin and making the knife handle into a weapon as I snipped and hacked at the meat beneath our hands.

“Gently, sister,” she said. The knife she held wavered. “I raised my younger brother Andreas.” I hesitated, reluctant to ask if there was an elder brother or sister, but she resumed speaking. “He is not like me. At all. Now, to your knife, sister.”

“I want a family,” I blurted. Beyond the aging sisters, I meant; beyond even Francesca. The hush of the kitchen’s walls and the garden’s fences chafed, and I jumped when the bell tolled in the tower, the notes rolling out, past the walls. “Don’t you want to know the world? See the faces of the people you feed?”

Francesca just shrugged her heavy face skyward. “Pray.”

I was young. Arrogant. I didn’t pray so much as issue orders. Show me how to have a family, Mother, I want to see lives changed by You! Nothing changed, no burning bush, no mighty reverberating voice or even a renewed whisper in the moonlight. No orphaned children appeared, requiring succour. No mysterious partner-to-be knocked on the convent door, offering to father my children. I knew better, I decided, and I left two months after my thirty-third birthday. I went penniless. Nuns swear to poverty along with the other vows. Poverty seemed no great sacrifice. But Francesca sent me to her younger brother in Vancouver. “Andreas will help you,” she said, a small hook in her voice. “He is a businessman, a ‘venture capitalist’, he tells me, so expect to pay for his help.”Andreas looked the polar opposite of his sister. Fine-boned and dapper. Silk scarf and a trilby hat on silver hair, a jaunty set to it. On the rack beside the kitchen door, a row of colourful jackets. A guitar leaned against the dining room wall. Piaf ’s voice, familiar since my childhood, on the stereo. “Je ne regrette rien … ”

Somewhere inside his bright ground-floor apartment, a door slammed.

“Sister. One moment.” He disappeared and I heard low voices, just a murmur. I peered over my shoulder as Andreas shepherded me out, a large wicker basket in his hand blocking my view of the door closing. Through the patio door, I saw the silhouette of a clean-cut head.

“So good of you to meet me here at home, the office is too far from the waterfront,” he said cheerfully. “To the beach!” We ambled to nearby English Bay, and Andreas offered me dark-roast coffee from a thermos in his basket. Of course he already knew that Francesca had taught me the family trade. “Indeed, sister,” he said, “I have some protégées, mostly younger than you, I suspect. One is an extraordinary baker, you must meet her. Here, try this,” he said, proffering pain au chocolat in a meticulously pressed linen napkin. “So. An outdoor cart, Francesca suggests. Or perhaps a café?” Aghast, I shook my head. “Indeed, you may be right, a café is too much, even for a healthy woman in her — what? — thirties?” He pursed his lips and eyed my hands and wrists, still tanned from the convent garden. His mouth made a small moue, approval or disdain, I couldn’t tell which. “Perhaps as Francesca suggests, an outdoor investment this time. Not a food truck, no, no, we want something petite, something charming, sufficient unto the needs of one small former nun. What about a little vending cart on wheels with wrought iron trim and maybe a roll-up canvas awning?” He paused. “Yes, just the thing, sister. Do you wish that we paint your given name on the awning?”

“Abigail? No one calls me that,” I said, my mouth full of pastry. He would carry on calling me Sister for years. “Our Sister of the sausages,” he would say, and ultimately, his joke became the fact, “Sister’s Sausages” recorded on the cart’s awning in flowing script.

Shock was settling into my body, numbing my hands, silencing me. Francesca had suggested that Andreas would help me, but I hadn’t imagined how, thinking vaguely of a secretarial job, maybe a position in a church outreach ministry. Even as I drank his espresso and ate his croissants, it didn’t occur to me that finding me a role in a church would never cross Andreas’ mind, just as the possibility of having my own business would never enter mine. But so it was to be.

Andreas briskly patted my arm. “A deal, yes, sister?” All I could do was nod. “I will charge you some small strictly nominal interest,” he went on. “Perhaps redeem a favour or two when I need sausages for my dinner parties. And here, my little welcome gift.” He pulled a stainless steel espresso pot from the basket and held it out. “Do you have any family in Vancouver?”

I shook my head. “All dead. Just Francesca.”

“So. We are family now.”

That’s how I became a street hawker. Francesca sent me her old meat grinder, the extra she kept under her bed just in case. Andreas found me a ground-floor furnished suite in subsidized housing near Main Street, with, wonder of wonders, a tiny gated yard.

“I had to pull a few strings,” he said as we walked through the suite a week later. “And I will pay your rent until you establish yourself.” He added more numbers to the tidy column beside my name in the little red book he carried in his jacket pocket.

“I may never be able to pay you back,” I said dubiously. The apartment alone, even on the east side, never mind the red cart and awning, cost more money than I had ever anticipated having during my convent life.

“Not to worry, sister. I will take

care of you, as Francesca asked. I had a good year, indeed I did. A healthy tax write-off keeps me good with my sister, and with her God. Keep your receipts. Now tell me, do you enjoy baseball? No, I supposed not. Ah well.”

The city made me get a licence, and more numbers went into the red book.

“Research!” Andreas said, and handed me cash. I found a butcher with good pork, made test sausages, and invited my benefactor over to sample half a dozen varieties, ultimately settling on his sister’s traditional bratwurst and my own ale and onion links.

After my cart became established on Cambie Street, in the lea of City Hall, beside a tiny park, he came by regularly, with an attractive young woman or youth on his arm, rarely the same person from one week to the next. Protégées, he said, never claiming any as his lover. On the summer day he introduced Elise and her sister, Patrice, both pale and narrow-hipped, I remembered the pain au chocolat I had tasted at our first meeting, and commissioned Elise on the spot. Handmade crusty rolls fit for my handmade sausages.

The neighbourhood cats and characters adopted me. I could see the cascade of buildings down the slope toward False Creek, and The Lions cut out against the sky to the north when the clouds cleared. I fed the same customers each week, frequently when the weather was fine, less so when the sky was cranky with rain. When the city expanded the transit line, and the new SkyTrain stop was added, my business leaped forward, and I saw how my small good daily works of smoked sausages made my customers smile. But there was never a special smile for me. I was always lonely. Sundays, I spent my afternoons at the community kitchen, making soup for the homeless women and their hungry children who crowded in, looking for beds and reassurances. The women, their faces aging beyond their years, needed the Mother even more than I did. Everywhere I looked, want and hunger were ahead of me. To even consider spending time searching for a special friend was out of the question in the face of such need; a woman like me could fill her days cooking, feeding, and the hunger would never be fed.

I had mornings to myself as I packed my coolers with sausages and condiments, humming to Verdi, records I found at the thrift shop for pennies, and a vintage record player too. One day in my kitchen, some weeks after I had met the black-eyed boy, I bent over the mortar and pestle, garlic and nutmeg fragrant in my nose while my espresso pot burbled and spat. In its curved silver face I saw my reflection pull into a jester’s grimace as knives plunged into my chest. I buckled to the floor, my chest compressing, heard the pot tumble, the gush of liquid against the tiles, Rigoletto caught in the skipping grooves.

Andreas found me an hour later on his daily coffee-klatsch swing through the neighbourhood. His companion stood in the background, a sleek young man in brown silk, eying my open cupboards with a scarcely hidden sneer while Andreas fussed.

“Sister! Such a terrible thing!” he said, kneeling beside me and gesturing at the silk suit to lift the needle off the record. “An embolism, perhaps. Or your heart. This is serious. We must get you to the clinic. My nephew will call an ambulance.”

I demurred, befuddled by the image of Andreas with a mop in his hands, tidying my kitchen floor, and the pains eased soon enough. It took a day or two before his choice of noun came back to me: “nephew.” Andreas had one sister, and she was childless. But my confusion faded along with the pain, and it didn’t matter.

My recurrent pain is far from my thoughts on a cloudy summer afternoon. A few months have passed since the unknown boy begged a sausage from me, and I’ve run out of maple syrup and garlic. So I take the bus to the market beneath the Granville Street bridge. Walking back, stopping in at Elise’s bakery, fragrant with yeast and sugar and chocolate, perched beside the cobbled path along False Creek, I hand Elise a cooler packed with bratwurst. She looks white and thin, skin etched with the charcoal of fatigue.

“How is Patrice?” I ask. “How is her appetite? Shall I bring weisswurst for her next week? They are mild.”

She wraps half a dozen pain au chocolat in parchment, shrugging as she ties a string around the package and passes it to me. “Patrice can’t eat anything after chemo, sister. And Andreas wants me to expand. He says it’s time for us to make some real money on his investment. I can’t. It takes all my energy just to care for Patrice. She’ll be in a hospice soon enough. But the idea of managing more staff makes me cringe. I can’t possibly. Not now.” She rubs her hands on her face, leaves a smear of flour under her shadowed eyes. “I owe Andreas everything, but you know what he’s like. I feel so guilty at the idea of saying no. Nothing to do with you, sister. Sorry to burden you.” She gives me another packet. “Here. For the birds.”

As I walk along the seawall, I’m thinking of Elise and her dilemma, caught on the rocks of a dying sister and business obligation. And Andreas, oh yes, I do indeed know what he’s like. It’s taking me years to repay his loan, although to his credit, he never chastises me for missing the odd month. Throwing bits of stale bread to the shrieking gulls, I ruminate about the open hands of those forces that surround others: parents, business partners, siblings. Children. I’ve been out in the world for a decade, and beyond the small needs of my cart, I still have few ties to bind me. I feel the lack keenly.

Watching the arc of birds across the sky, I trip on an uneven cobble. My ankle twists beneath me, and I tumble to my hands and knees, land in a puddle, my pastry and groceries askew across the path. So here I am, scrambling around, relieved the maple syrup is still intact in its glass jar, gathering up the garlic, my nose inches from the stones, mildly cursing the birds and my own inattention, when I hear a voice.

“Help you?”

I look up to see the lovely black-eyed boy of the park. Of the surprise kiss. He grins and holds out one hand, helps me up and eyes my pastries while I shove everything back onto my tote, but I don’t argue when he pulls the bag from my hands, the sting in my ankle shouting for ice. My groceries knock against the battered guitar on his hip all the way back to my suite, and when I try to thank him, that wide white smile blooms. As he leaves, I give him two croissants.

He finds me at the cart again the next day. He’s fifteen, looks twelve, nobody to love, a street kid with a Québécois accent. Sylvain. Around massive bites of bratwurst, he tells me about his lost Maman. As I listen, I send a prayer into the ether, a wordless thank-you to her and to the Mother. For his sake, and for mine.

“She was a yoga teacher, eh, and when we get Vancouver we were broke. She leave me with her girlfriend, for just the evening, t’sais, and she go to the park. Not this petit.” He waves an expansive hand at the park we sit in. “The big one by the water.”

“Stanley Park?”

“Oui.”

“Had she left you alone before? To go to the park?”

His face closes. “Maybe. This time, she die. Stabbed, hmmm. And now I am just me alone. I keep away from La Welfare, they want to put me with some strangers.” He’s surprisingly sanguine. Somehow he has learned to trust in the universe, and he is still whole, still safe. The Mother is watching this French sparrow.

I watch over him too, he’s raggedly thin. He visits me just before I close up every afternoon, always hungry, with a motley entourage of boys in tattered jeans and outgrown runners. I feed them, all the sausages they want, even though each bite means less cash towards paying back Andreas. The boys enjoy my company, and after they finish eating they lounge on the cement planters and stairs that flank the street, Sylvain perched close to my cart. We feed the birds and he tells me about his mother’s meetings with famous movie-star yoga devotees, then he plays his guitar and sings, his high voice rippling melodies into the clouds.

I don’t know where Sylvain sleeps. Prying goes against the privacy I learned in the convent, but a beautiful boy like him must take risks to survive. I am afraid to ask. I don’t want to know. I start bringing extra croissants, apples and yoghurt with me, and it isn’t long before he puts on a few pounds, and soon he’s left the street lads behind and is sleeping on the couch in the living room. Then

I teach him how to make sausage. He’s curious, with quick fingers and a nimble mind, and he especially loves the smoker I have bolted onto the fence around my yard, a hinged metal box contrived with parts Andreas’ handyman found for me. Sylvain likes to feed applewood into the firebox and smell the sweet smoke when the fire slows, links of sausages dangling above the coals. It reminds him of the sugaring-off at home, he says, the fire and the buckets of maple sap, the thickened syrup congealing. Before the summer winds to a close, I have him smoking sausages on Fridays, selling at the cart with me on Saturdays.

All this long wet autumn, on my weekly visits to Francesca, I take him with me on the SeaBus across the harbour to North Vancouver. Francesca, who has risen to Mother Superior in the convent, smiles at him as he fidgets in the chapel, nods over his head at me, and sends us back across the water with bags bulging, heaped full of chard, wild mushrooms, arugula, onions, beets.

“Do you see my brother often?” she inquires one afternoon as we step into the late October gale. “Does he still love baseball? Is he still alone?”

“Oh, I see Andreas every week, for coffee. He’s fine.” I’m so happy to show off my boy that I forget to mention Andreas’ “nephew,” and it slips my mind until we get home. Sociable Andreas, never alone. I forget about her query.

It’s clear that Sylvain doesn’t like Andreas when they meet. I’ve told Andreas about my new family member, and he arrives with a gift in hand, a black and gold baseball jacket, eyes Sylvain closely as he holds it out to him. Sylvain puts his hands behind his back, and Andreas drapes the jacket on a chair.

“Looks like it should fit,” he says, his nasal voice flat and non-committal. “Perhaps your new friend would like to come to watch the ballgame in the park with me some evening next spring when the season gets going, sister? I always have an extra ticket. What say you, Sylvain? Have you seen the city’s baseball team, the Canadians, play at Nat Bailey Stadium?” When Sylvain doesn’t respond, Andreas looks at me, shrugs and carries on. “Ever hear of José Canseco? A hell of a hitter. He was a Canadian, once upon a time.”

What Can't Be Undone

What Can't Be Undone